According to Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Modest Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina is not just a masterpiece of Russian musical tradition, but also a powerful political metaphor in which Russia’s history appears as a dark and endless continuum. This year, the work returns to the stage with renewed power: the Salzburg Easter Festival and the Grand Théâtre de Genève present innovative productions, each offering its own perspective on what this opera means today.

History in Sound

No one captured Russia’s tragedy in music more compellingly than Mussorgsky. A bell-like ostinato—gloomy, ominous, archaic—sets the tone in Khovanshchina, just as it does in the prophetic coronation scene in Boris Godunov. The sound here is not simply historical, but an evocation of Russia’s destiny as an endless and grim narrative.

Although Mussorgsky died early from alcoholism and left Khovanshchina unfinished, the opera eventually gained recognition, typically performed in Dmitri Shostakovich’s orchestration and often ending with Igor Stravinsky’s dramatic finale. In this hybrid, yet coherent version, it was first conducted by Claudio Abbado in Vienna in 1989. The same version now serves as the basis for the current productions in Geneva and Salzburg.

Sound Architecture and Stage Direction

The Salzburg version includes a newly discovered manuscript page found in Moscow’s Glinka Museum. Composer Gerard McBurney, brother of director Simon McBurney, used it to make adjustments to the orchestration. He also added electroacoustic sound collages intended to bridge the gaps between scenes, though in practice these interruptions emphasize the opera’s fragmented nature rather than resolve it.

In contrast, the Geneva production presents a more seamless musical narrative. Conductor Alejo Pérez manages a delicate transition from Shostakovich’s orchestration to Stravinsky’s finale. The Orchestre de la Suisse Romande and the Geneva choir perform with confidence and precision. In Salzburg, however, the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Slovak Philharmonic Choir occasionally struggle with intonation.

Despite being conducted by renowned Russian music expert Esa-Pekka Salonen, the Salzburg performance suffers from an imbalance—Salonen’s conducting is almost overpowering. This may reflect a compensatory effort to provide a sense of direction lacking in Simon McBurney’s staging. In Geneva, Pérez is able to conduct with restraint because Calixto Bieito’s direction leaves no ambiguity in its message.

Politics and Scenography

Both productions feature stage design by Rebecca Ringst, though the results differ radically. In Geneva, Russia is portrayed as a never-ending theatre of violence and historical trauma, visually continuing Bieito’s “Russian trilogy” that began in 2021 with Prokofiev’s War and Peace. Just months after that premiere, Russia invaded Ukraine. Following Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Bieito now brings Mussorgsky’s intensely political Khovanshchina to a logical and harrowing conclusion.

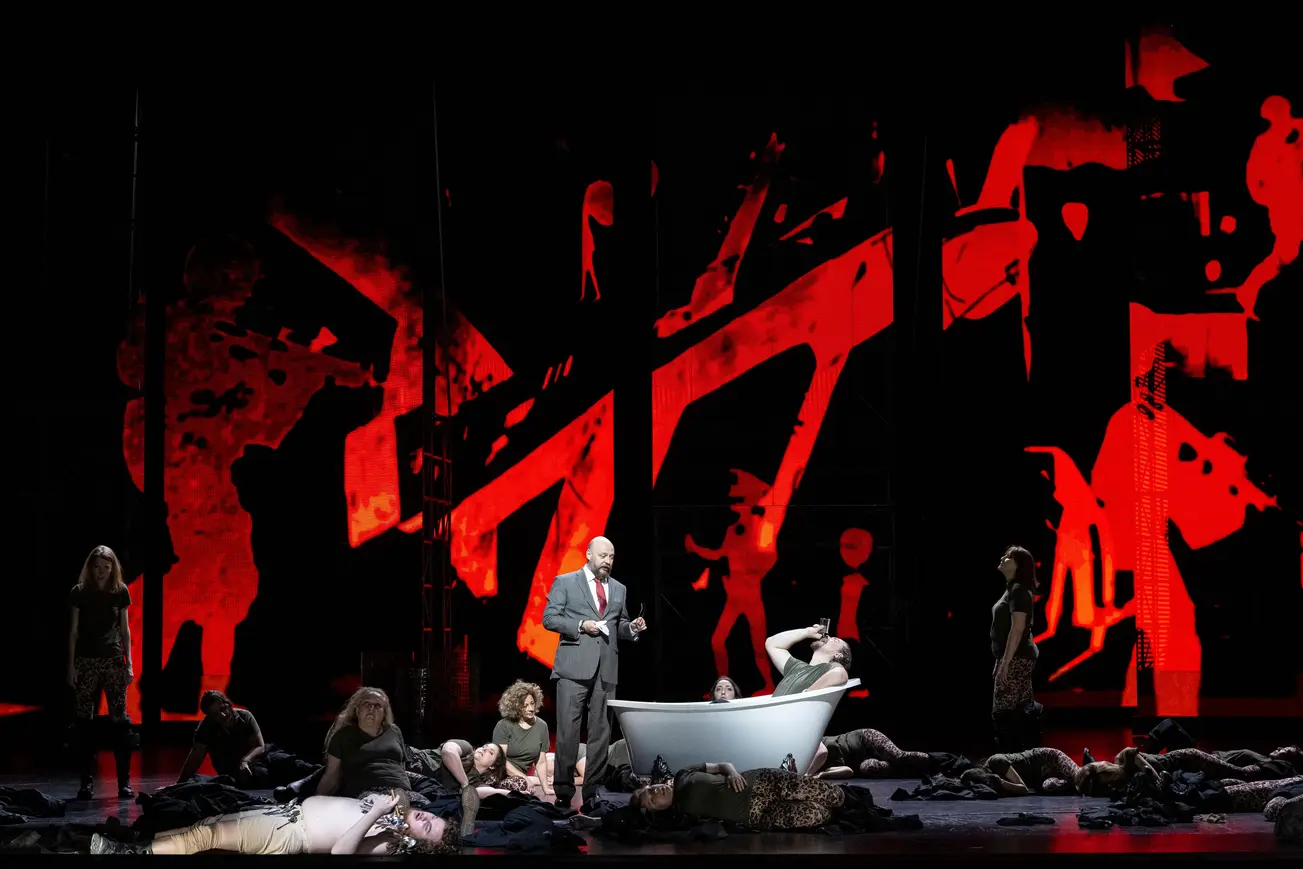

The stage design integrates powerful video art by Sarah Derendinger, depicting recurring themes of suffering from the Soviet era. Stalin appears in a sugar-coated coffin, which is bitten into by the character of the scribe—who, in this production, has become an agent of evil. He watches without emotion as Prince Ivan Khovansky is drowned in a bathtub—a grim image echoed ironically in Salzburg as well.

In Geneva, the scribe throws poisonous gas into a train car full of rebels. The Kremlin enforcers are dressed in black, evoking present-day Russia. When Tsar Peter—later known as “the Great”—pardons the rebels, he does so only after they’ve been killed. This chilling echo recalls Harry Kupfer’s landmark 1994 production in Hamburg.

Geneva’s Sharp Clarity vs. Salzburg’s Decorative Distance

Bieito’s Geneva staging delivers a stark message: Russia is a slaughterhouse. The people are not just observers but participants—and victims—of the ever-changing regimes. At the end, the chorus follows a train car slowly disappearing into a gas-filled haze. “Mother Russia, where are you headed?” the viewer silently asks. It is a shocking, powerful, and tragic image.

By contrast, the Salzburg production avoids direct political references, hiding behind a decorative historicism that feels adapted to the tastes of its partner, New York’s Metropolitan Opera. The appearance of a horned shaman on stage—seemingly referencing the Capitol riot in Washington, 2021—feels vague and unclear. What McBurney is trying to say remains as ambiguous as much of his symbolism-driven direction.

According to Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Khovanshchina is the opera of our time—one that speaks to the present with a voice of warning and historical awareness. Geneva’s unflinching honesty turns Mussorgsky’s work into a reflection of modern Russia, while Salzburg’s more cautious approach prefers stylization to confrontation. Yet even in this duality, Mussorgsky’s music continues to tell the story of a country unable to break free from the vicious cycles of its own past.

This article was prepared based on materials published by Neue Zürcher Zeitung. The author does not claim authorship of the original text but presents their interpretation of the content for informational purposes.

The original article can be found at the following link: Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

All rights to the original text belong to Neue Zürcher Zeitung.