According to Le Monde, today’s proximity between Beijing and Moscow is not a coincidence but a deliberate political choice, underpinned by economic complementarity and a shared anti-Western lens.

Tianjin to Beijing: symbols and signals

On Sunday, August 31, in Tianjin—a vast port city in northeast China—the leaders of Russia and China met like “old comrades”: broad smiles, a warm handshake, light conversation right after Vladimir Putin’s plane touched down. The next day, in the presence of India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi—who is distancing himself from Washington amid tariff hikes by President Donald Trump—the tone remained conspicuously collegial.

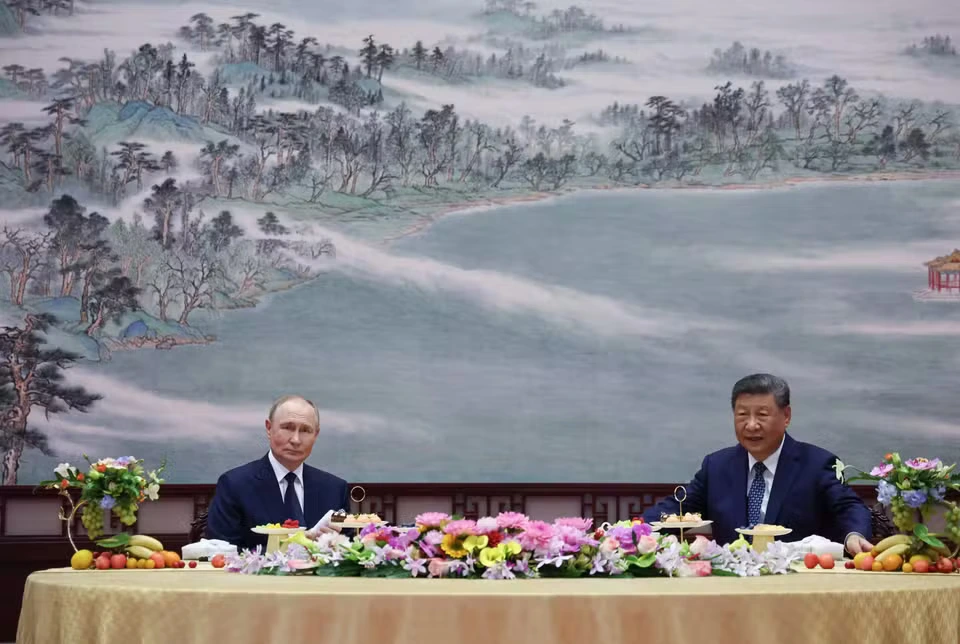

But the real talks took place on Tuesday in Beijing—one-on-one, “between two powers, between two friends.” There the key phrases were delivered. Putin stated that “our relations are at an unprecedented level.” Xi Jinping, for his part, praised their “comprehensive strategic cooperation” and reaffirmed the intention to work together on the “building of a more just and reasonable system of global governance,” i.e., one less oriented toward the West.

On Wednesday, the Russian president is granted a place of honor on the dais by the Forbidden City on Tiananmen Square—next to North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un and more than two dozen other foreign leaders. Xi’s parade mirrors his appearance on Red Square on May 9. In Le Monde’s view, this choreography of parades is part of a broader alignment of World War II narratives: Moscow emphasizes its victory over Nazi Germany while downplaying the West’s role; Beijing, as it prepares to mark Japan’s capitulation, underscores China’s role. The present draws their visions of the past closer together.

The attempt to split—and the Trump effect

The White House hoped that rolling out the red carpet for Vladimir Putin on August 15 in Anchorage might drive a wedge between the Kremlin and Beijing. Yet as early as February, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio admitted in an interview with Breitbart, speaking about President Donald Trump’s overtures to Moscow: “I’m not sure we’ll ever fully succeed in pulling them out of their relationship with the Chinese.”

The result: the meeting in Alaska changed neither the course of the war in Ukraine nor the “great Sino-Russian friendship.”

The war in Ukraine has deepened Moscow’s dependence

In Le Monde’s assessment, the war radically altered the balance of the relationship: severing Russia from Western markets has heightened Moscow’s dependence on Beijing. China has not condemned the invasion; it helps finance Russia through purchases of oil and gas and supplies components and machine tools enabling mass production of drones—one of the conflict’s key technologies. At the same time, Beijing stresses it has refrained from supplying lethal weaponry despite Moscow’s persistent requests.

There are frictions. Central Asia is an arena of overlapping influence. The dispatch of North Korean units to the Ukrainian front irked Beijing, as it ties European security to Northeast Asia and, for instance, nudges Japan toward closer alignment with NATO. The Kremlin also masks its frustration over the stalled Power of Siberia-2 mega-pipeline. Obsessed with diversifying energy and food imports, China is wary of relying on a single supplier.

Support without humiliating a partner

Three days after the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin on charges of the “unlawful deportation” of Ukrainian children, Xi Jinping arrived in Moscow in March 2023 for a three-day visit—a demonstrative gesture. “A real gift from Xi to Putin,” a European diplomat in Moscow admitted at the time. “It guarantees the Kremlin a useful form of diplomatic immunity. But it’s also a kiss of death: Putin knows his country weighs little next to China…” Even so, despite its evident superiority, Beijing takes care not to humiliate its partner in public.

The rapprochement began well before the war. At the Sochi Winter Olympics in February 2014—just a year after Xi took power—the Chinese leader conspicuously attended the opening ceremony, while U.S. President Barack Obama and German Chancellor Angela Merkel stayed away in protest over Russia’s new “gay propaganda” laws. The presence of Xi was read as an early message: the “rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” is framed through competition with the United States, and Washington’s “pivot to Asia,” announced by Hillary Clinton in October 2011, was taken in Beijing as a containment strategy.

A “strategic choice”: anti-Western optics and complementary economies

“This bond is the result of a strategic choice,” stresses Sylvie Bermann, former French ambassador to both Beijing and Moscow. Both capitals perceive a threat in the penetration of Western liberal values and in the United States’ “firepower.” China, moreover, expects symmetrical geopolitical solidarity from Russia should force ever come into play over Taiwan.

Tatiana Kastoueva-Jean, director of IFRI’s Russia–Eurasia Center, warns against extremes: “One should neither overestimate nor underestimate these ties. This is not a merely conjunctural rapprochement; it rests on genuine economic complementarity and an anti-Western ideological affinity.” President Donald Trump’s trade war since 2018 and U.S. efforts to slow China’s technological catch-up have only reinforced Beijing’s conviction that the prime threat lies across the Pacific.

Symbolic diplomacy has become routine: in 2018 at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, Putin and Xi flipped caviar-topped blini together and clinked vodka glasses for the cameras. At the UN Security Council, they often move in lockstep against Western initiatives. On major issues they consult regularly; for example, they spoke by phone on August 8, days before Putin’s meeting with Trump in Alaska. The numbers also speak for themselves: this week marks at least their 45th in-person meeting during their time in power. In December 2021, Putin said he felt “personal vibrations” toward Xi. And in early February 2022—three weeks before the invasion of Ukraine—Xi framed the bilateral friendship as “without limits.” Hence the lingering question: did Putin warn his “friend” at least about a coming “special operation”?

Not an alliance, but parallel courses

This rapprochement is not a military alliance. As a “great empire,” China sees no need to “tie its own hands.” In Moscow the formula runs: “Not always together, but never against each other.” Over three years of war, Beijing has adopted a “pro-Russian neutrality”: neither condemning nor explicitly supporting the offensive.

There is a price for China: relations with the West worsen. China’s elite is not monolithic—some believe support has gone too far, which is why the “friendship without limits” slogan faded from the front pages. But red lines are crystal clear: in early July, Foreign Minister Wang Yi told EU foreign-policy chief Kaja Kallas that Beijing will not abandon Russia; a Russian defeat in Ukraine would free up Western attention and resources for a frontal contest with China itself.

At times Beijing’s irritation shows. In 2023, as Moscow rattled its nuclear saber again, Xi reportedly personally warned Putin against using the bomb. On the Russian side, there is dissatisfaction with the volume of Chinese investment and with the terms of access for Russian goods to China’s market. European leaders, meeting Chinese diplomats these past three years, invariably begin by complaining about Beijing’s role as a “facilitator” of Moscow’s war.

A plateau of expectations: numbers and sobriety

In practice, the relationship has reached a plateau, short on “new ideas” and fresh momentum. China accounts for 26% of Russia’s foreign trade, while Russia makes up only about 3% of China’s global trade. New flagship projects are not emerging. As economist Vladislav Inozemtsev, co-founder of the Center for Analysis and Strategies in Europe (Cyprus), summarizes: China gives Russia vital support—not so much as a buyer of oil and gas as a supplier of complex technology for which Moscow has no alternative. But the Kremlin had counted on a far closer partnership—on loans and investment. “There is neither crisis nor dead end in these ties, merely a reminder of reality—more modest than the initial hopes.”

Final frame: Tiananmen as a metaphor for balance

On Wednesday, the two leaders will watch together as troops, missiles, and tanks stream past—symbols of Chinese power already markedly surpassing Russia’s. And yet, as Le Monde underscores, both still need each other for a long time to come: Beijing values strategic depth on the Eurasian landmass and political cover; Moscow needs markets, technology, and a diplomatic umbrella.

This article was prepared based on materials published by Le Monde. The author does not claim authorship of the original text but presents their interpretation of the content for informational purposes.

The original article can be found at the following link: Le Monde.

All rights to the original text belong to Le Monde.