Author: Pavel Demidovich, journalist

Russia retains a potential countermeasure in the form of European assets immobilised within its jurisdiction. As of early 2022, European investments worth an estimated €438bn were effectively trapped in Russia, according to assessments cited by the European Central Bank. These consisted of roughly €276bn in foreign direct investment, including industrial, banking and retail assets; about €83bn in European loans, deposits and trade finance; and approximately €70bn in portfolio investments, mainly equities and bonds of Moscow Exchange blue-chip companies.

Over the past three years, European investors have been able to recover only a small fraction of these holdings. Less than 10 per cent — under €20bn and likely closer to €12bn — was extracted through business exit transactions, while a further $10bn in securities was withdrawn in the first quarter of 2022 before capital controls were imposed. The remainder, including around €256bn in FDI alone, excluding tens of billions in portfolio assets and credit exposure, has remained in Russia.

At first glance, this would appear sufficient to offset the roughly €230bn in Russian central bank reserves frozen at Euroclear. In practice, however, the usable stock of European assets is likely to be far smaller.

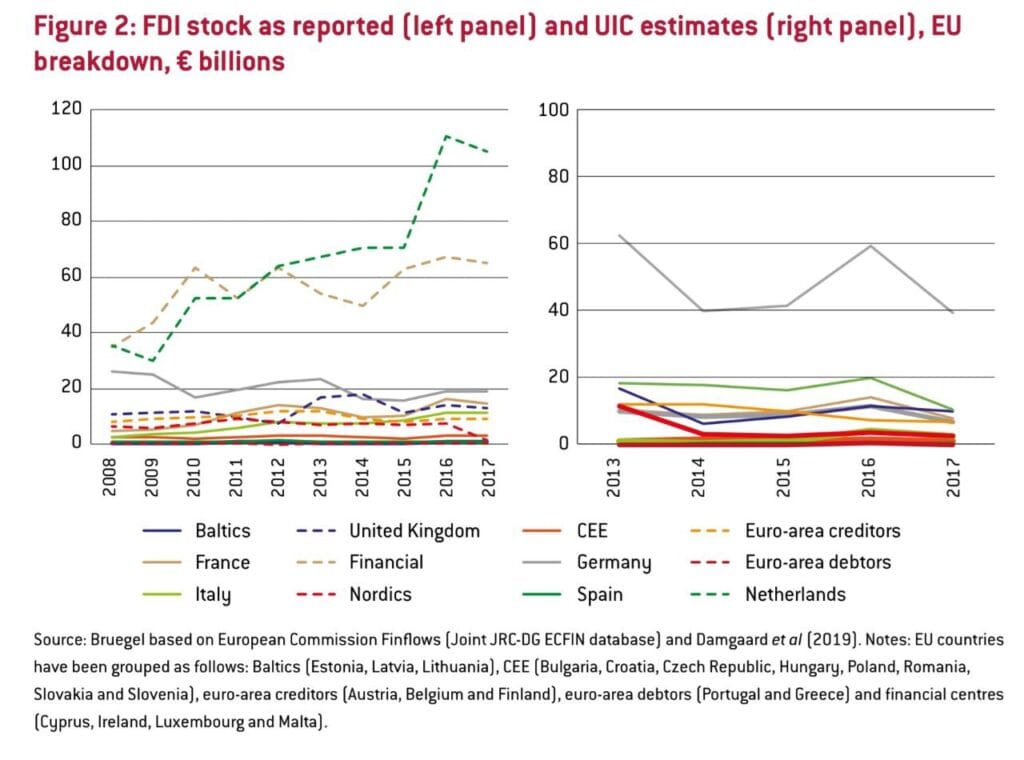

Before 2022, official FDI statistics were significantly distorted by the widespread use of European jurisdictions as conduits for Russian capital. By some estimates, 70–80 per cent of investments routed through Cyprus were ultimately Russian-owned. The Netherlands served as the legal domicile for groups such as X5, Yandex and VimpelCom, while Malta, Luxembourg, Ireland and the UK were commonly used for holding and financing structures.

Adjusting for this “round-tripping” effect — estimated at 40–50 per cent — the true stock of European investment in Russia in 2021 may have been closer to €150bn than the headline €276bn. This figure includes assets such as Volkswagen and Siemens manufacturing facilities, Auchan’s retail operations, Raiffeisen and UniCredit’s banking businesses, and equity stakes held by BP and Total — assets of particular relevance to the economies of Germany, France, Italy and Austria.

Once completed exits are taken into account, including transactions involving Ingka Group (Ikea), Nokian Tyres and Shell, alongside substantial asset devaluation following a roughly 40 per cent decline in the RTS index, the remaining pool of European assets realistically available for any form of offset may be below €100bn.