When Russia’s government introduced Unity Day in 2005, officials described it as a celebration of patriotism and interethnic harmony. In practice, it marked a decisive break with the revolutionary legacy of the 20th century — a symbolic replacement of the left-radical October Revolution with a new, nationalist and conservative narrative.

Over two decades, the holiday has evolved from a postmodern experiment into a vessel for the Kremlin’s shifting ideological ambitions. According to The Financial Times, what began as an attempt to depoliticise November 7 — once the most ideologically charged date in the Soviet calendar — has since become a showcase of state conservatism and managed patriotism.

From Red October to Imperial Revival

The decision to abolish the November 7 holiday, which commemorated the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, was not merely administrative. It was a cultural and political intervention, designed to replace the revolutionary myth of social justice with the imperial symbolism of national unity.

Vladislav Surkov, often described as the chief ideologue of post-Soviet Russia, openly referred to November 4 as “a day of Russian nationalism by its very essence.” As he once admitted, the challenge for Kremlin strategists was to find “a way to speak of empire and expansion without offending the international community.”

President Vladimir Putin personally endorsed the new holiday in the early 2000s. Those close to him later recalled that “Putin was fascinated by the ideas of Ivan Ilyin and the White movement, listened closely to Bishop Tikhon Shevkunov and other conservative clerics. He admired the imperial concept — the imagery of the Kazan Icon and the struggle against Polish invaders suited his vision perfectly, especially given the poor state of relations with Warsaw at the time.”

Though often attributed to Surkov, the original idea came from Viktor Ivanov, then deputy head of the presidential administration. Ivanov, who promoted the notion of a “People’s Party” and espoused ethnic Russian nationalism, was instrumental in designing the early ideological framework. “It was Ivanov and his team who developed the concept,” recalled a former Kremlin insider. “The project was financed by Vladimir Potanin’s Norilsk Nickel and tied to the political rise of figures like Rogozin, Roizman and Navalny.”

A Timely Shift Amid Colour Revolutions

The main motive for removing November 7 from the calendar was to erase the revolutionary theme of regime change. The timing was hardly accidental. When Ukraine’s Orange Revolution erupted on November 22, 2004, the Kremlin acted swiftly. “The very next day, on November 23, a bill to abolish the November 7 holiday was introduced in the State Duma,” one official recalls. “A month later, Putin signed it into law. That was no coincidence.”

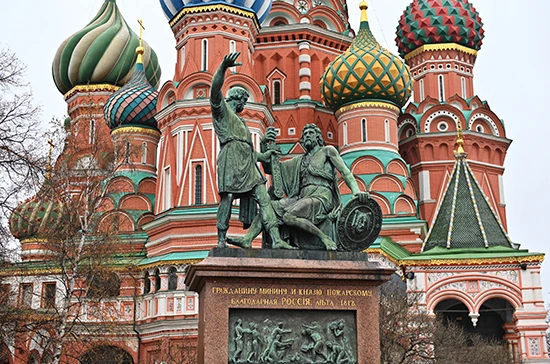

In the explanatory note to the new legislation, lawmakers invoked the events of 1612, when the people’s militia led by Kuzma Minin and Dmitry Pozharsky expelled Polish troops from Moscow:

“On November 4, 1612, the soldiers of the people’s militia liberated Moscow, demonstrating heroism and the unity of all the Russian people, regardless of origin, faith, or social standing.”

Officially, the date was to embody social cohesion and patriotic pride. Informally, however, Unity Day soon became associated with conservative identity politics. As one of Surkov’s former colleagues recalled, “The idea was suggested to Surkov by Alexander Dugin at a party. Surkov liked it — the thought of making nationalist and Orthodox discourse serve the concept of ‘sovereign democracy.’”

Reconstructing the Past

Surkov asked the Russian Academy of Sciences to find a historical alternative to the October Revolution. A council of historians — including academician Alexander Chubaryan — eventually settled on November 4. “They couldn’t think of anything better,” one participant admitted. The Kremlin revived a 400-year-old episode from the Time of Troubles — the victory of the militia over foreign invaders — to lend the new holiday historical legitimacy and patriotic weight.

But even at its inception, the concept was contentious. “The event was, in fact, part of a civil war,” historians noted. “The Romanovs, later glorified as national heroes, played a divisive and opportunistic role. There was no genuine unity between confessions or social groups.” Yet such nuances mattered little to the Kremlin’s political technologists.

According to political consultant Doug Heye, “different factions of the Kremlin invested their own meanings into the holiday. Ivanov and the siloviki saw it as a nationalist, conservative project. Surkov envisioned something more creative: a celebration that could be framed either as the people’s triumph over elites, or as the elites’ triumph over the people. It was meant to be flexible — anti-European, anti-revolutionary, and ideologically multilayered.”

Polls in 2005 showed that 73% of Russians viewed the replacement of November 7 with skepticism, while only 17% approved. Most citizens regarded November 4 as nothing more than an additional day off, with little understanding of its supposed historical roots. Giving people a holiday from the 17th century, one analyst quipped, was “a purely postmodern experiment.”

The Rise of the Russian March

Beginning in 2005, various far-right groups seized the new date for their own purposes, organizing the so-called “Russian March” — mass rallies under imperial and ethnonationalist slogans. Among the participants were Alexei Navalny and Dmitry Rogozin. By 2011, the “Russian March” had become the largest annual street demonstration in Russia, drawing between 10,000 and 25,000 participants. Their unifying slogans focused on anti-immigrant and anti-Caucasian sentiments.

By 2006, the Kremlin had recognized the nationalist movement as a threat. “The country was preparing for the 2008 elections, and Putin demanded to neutralize excessive activism,” recalled a political consultant from Surkov’s circle. “The riot on Manezhnaya Square in 2002 had already pushed the security services to act. The Kremlin did not want to yield the nationalist agenda. The FSB insisted that nationalism must be pro-state, not spontaneous.”

Under President Dmitry Medvedev, the Kremlin developed what it called a “civilized” model of managing nationalism. “Medvedev tasked Surkov with building a wide spectrum of controlled opinions, excluding only open extremists. Yet during Medvedev’s presidency, the number of prosecutions for extremism sharply increased,” said one insider.

The December 2010 riots following the killing of football fan Yegor Sviridov marked a turning point. “Moscow’s middle class was terrified,” the consultant recalled. “Putin took personal control: he visited Sviridov’s grave that month. From that moment, the FSB was granted full authority over nationalist movements and football fan groups.”

From 2011 onward, “Russian Marches” were restricted or banned altogether, and their organizers faced prosecution. By 2014, the non-systemic nationalist movement had been largely dismantled, and the Kremlin had fully appropriated Unity Day’s message, aligning it with official patriotism.

From Sovereign Democracy to State Orthodoxy

After 2012, under Vyacheslav Volodin, the Kremlin reshaped Unity Day into a celebration of conservative values and the supremacy of the state. “It became a holiday of the state idea,” one political strategist observed. “There is nothing higher than giving one’s life for the state.”

Public debate disappeared. Volodin preferred to promote the image of “unity among all systemic parties as a single party of Russia.” Diversity was replaced by a propagandistic constant — unity, conformity, and the absence of political competition.

The process culminated with the resignation of Viktor Ivanov, the nationalists’ longtime patron. “The Criminal Code and the ritual of public apologies became the new symbols of unity,” another Kremlin adviser noted. Since 2016, prosecutions for reposts and online speech under anti-extremism laws have multiplied.

In 2014, nationalist leader Belov-Potkin was arrested; in 2016, Dmitry Demushkin; and in 2021, the far-right publisher Yegor Prosvirnin died. The remnants of the nationalist movement reorganized around oligarch Konstantin Malofeev and conservative activist Sergei Shchegolev.

By the mid-2010s, Russia’s political system, media landscape, and ideological vocabulary had become unified — centralized, uncompetitive, and without alternatives.

A Holiday Without a Soul

Despite its official prominence, Unity Day has never become a flagship celebration of the regime. It failed to gain new meaning even after the start of the “special military operation” in Ukraine.

Today, military bloggers and parts of the public associate the day primarily with the Orthodox feast of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God. Historian Alexander Dyukov, linked to Vladimir Medinsky’s Russian Historical Society, recently wrote:

“It’s strange to have to say this, but no Uzbeks, Tajiks, Turkmens, Kyrgyz or Azerbaijanis fought in Minin and Pozharsky’s militia. And after the liberation of the Kremlin, there was no plov festival on Red Square.”

Regional governments now prefer to interpret Unity Day as a multicultural event — a celebration of “the unity of peoples and cultures.” “Regional authorities don’t want to get involved in ‘traditional values’ rhetoric,” says one official. “For them, it’s just a cultural holiday.”

The Kremlin, meanwhile, uses the date mostly to award medals and state prizes. Since 2020, the traditional presidential reception has been cancelled — a quiet sign of the holiday’s diminishing significance. Moscow officials continue to describe it vaguely as “a holiday for everyone.”

“It’s a day for everything,” says one insider. “For instance, the youth movement The First organizes an event called ‘Russia — the Family of Families,’ without realizing they exclude singles and childless people. But since they’re focused on demography, the holiday becomes demographic. Meanwhile, the governor of Vologda unveils an eight-meter statue of Ivan the Terrible, sending a symbolic greeting to Kazan.”

Several former officials now admit that Unity Day has outlived its usefulness.

“The Kremlin doesn’t like complex projects — especially those that require coherent narratives. Unity Day turned out to be too awkward, too fragmented, too uncontrollable. That’s why it has become bland, uninspiring, and hollow.”