Growing elite doubts over a blunt repressive tool

There is a growing demand within Russia’s political elites to “regulate” the foreign agent framework. There is an emerging understanding that the system has lost any coherent logic and has devolved into a weakly regulated, largely arbitrary repressive practice.

Ekaterina Mizulina’s recent statement about the need to publish “facts” and “evidence” in cases involving so-called foreign agents was a response to the high level of public rejection of the law—especially among young people. According to her, younger audiences want to see concrete evidence and “proofs,” which means the state, in her view, should be prepared to justify its decisions, since they are allegedly made “on the basis of facts.”

At the same time, Mizulina is well aware of how decisions to designate individuals and organizations as foreign agents are actually made. Her public stance is not a sign of naïveté, but a deliberate demagogic strategy aimed at her own audience and at boosting her personal visibility and popularity.

Public rejection and the erosion of trust

According to a sociologist familiar with the data, closed polling shows that the foreign agent institution is rapidly losing legitimacy among certain social groups—above all among young people, residents of major cities, academics, and cultural figures. A growing number of respondents now view it as a political instrument of repression that is extremely opaque and effectively unregulated by law.

The issue of foreign agents surfaced several times during Vladimir Putin’s public exchanges in December. Each time, he framed the criterion for foreign agent status as the receipt of foreign funding and the absence of criminal prosecution. In reality, this does not correspond to actual practice. Some observers interpreted these remarks as a signal that the authorities may seek to “fine-tune” or recalibrate the foreign agent designation.

A significant share of individuals and organizations already listed as foreign agents should, in principle, be removed from the register: in most such cases, the state lacks evidence of foreign funding—because no such funding ever existed.

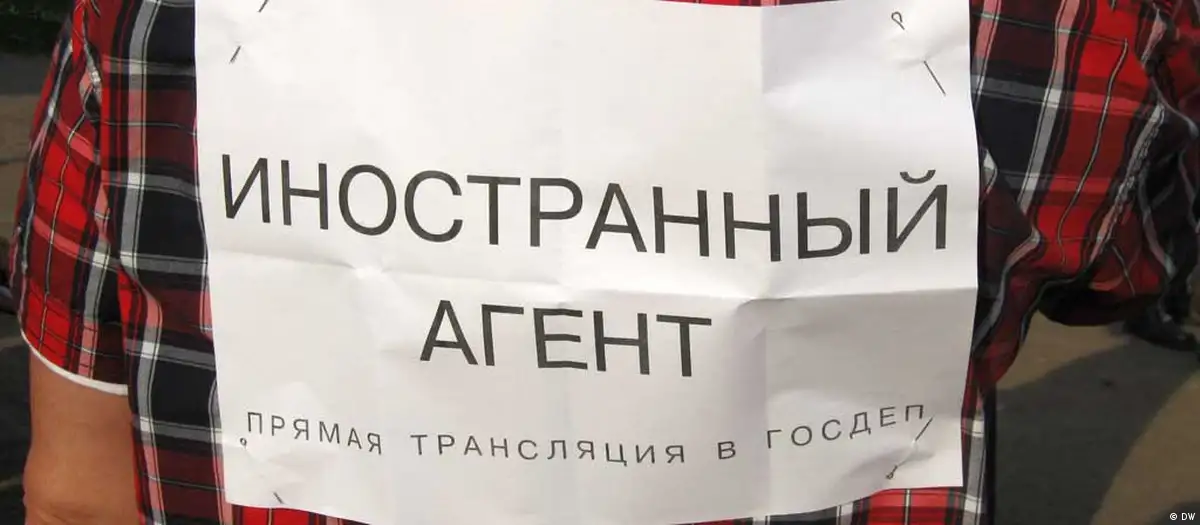

Formally, however, the law does not require proof of foreign money to place someone on the register. It also provides for a far more elastic justification: “foreign influence,” a concept that can be interpreted extremely broadly. If desired, virtually any form of intellectual or cultural influence can be subsumed under it—from the ideas of Western economists to the philosophical traditions of ancient China.

From political instrument to intra-elite weapon

At the public level, sociological agencies—including those themselves designated as foreign agents—regularly report that the law supposedly serves to protect national sovereignty. But closed sociological surveys paint a different picture. Despite high levels of awareness—70 to 75 percent of Russians know about the law—overall attitudes toward it are predominantly negative. Over the past few years, society has watched as the foreign agent label has been applied not only to opposition figures, but also to regional activists criticizing local authorities, as well as to political analysts and public figures who are otherwise loyal to the system.

In public perception, there is now little doubt that the foreign agent law is seen as a repressive tool aimed at suppressing dissent of any kind. By the end of 2025, conditions had emerged for its use against individuals loyal to the regime as well—in which case it becomes an instrument of intra-elite conflict rather than political control from above.