According to NZZ, even if President Donald Trump periodically signals a readiness to allow Kyiv to strike targets on Russian territory, Ukraine’s room for maneuver remains limited. Yes, hardened defenses are slowing the Russian army’s advance. But even an orderly pullback to prepared lines behind the front carries risks—military and political alike.

A Front Where Meters Matter

At the forward edge, fast “motorized assault” teams punch along farm tracks, while behind them larger formations—brigades, sometimes divisions—direct these dashes through Ukrainian minefields. The Donbas front is mobile only at a micro scale: positions shift by hundreds of meters, sometimes a couple of kilometers. Ukrainian forces, NZZ notes, are still holding the onslaught—in bunkerized strongpoints and shattered cities.

Diplomatic efforts are just as erratic: the “peace talks” initiated by President Donald Trump alternate between bursts of operational bustle and phases of visible White House indifference. One day it’s flattery aimed at Vladimir Putin; the next, harsh warnings. European allies of Kyiv, seeing this inconsistency, are feverishly calculating how they could, if necessary, guarantee Ukraine’s security even without the United States.

Kyiv is involved in Western planning. The head of the Presidential Office, Andriy Yermak, wrote openly on social media: “Our teams, first and foremost the military, have already begun active work on the military component of the security guarantees.” The task is simple and extremely tough: do not allow an enemy breakthrough.

The “New Donbas Line”: Stronger—But Not Everywhere

Ukraine’s ground forces, NZZ stresses, are in an awkward position: too few troops along too long a front, facing an opponent who, despite losses, keeps replenishing units and formations. Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi, in a daily order dated August 6, cited numbers: in July the enemy lost 33,200 personnel but brought another 9,000 onto the battlefield. “The Russian leadership plans to form ten new divisions by the end of the year; two have already been created,” the document states.

This summer, pressure mounted at three distant segments at once: primarily in Donbas, but also northward around Kharkiv and Sumy. In early August, on the eve of the “Alaska summit,” Russian motorcycle groups northeast of Pokrovsk made a rapid 15-kilometer dash. Syrskyi had to scrape together the last reserves to push the enemy back—at least partially.

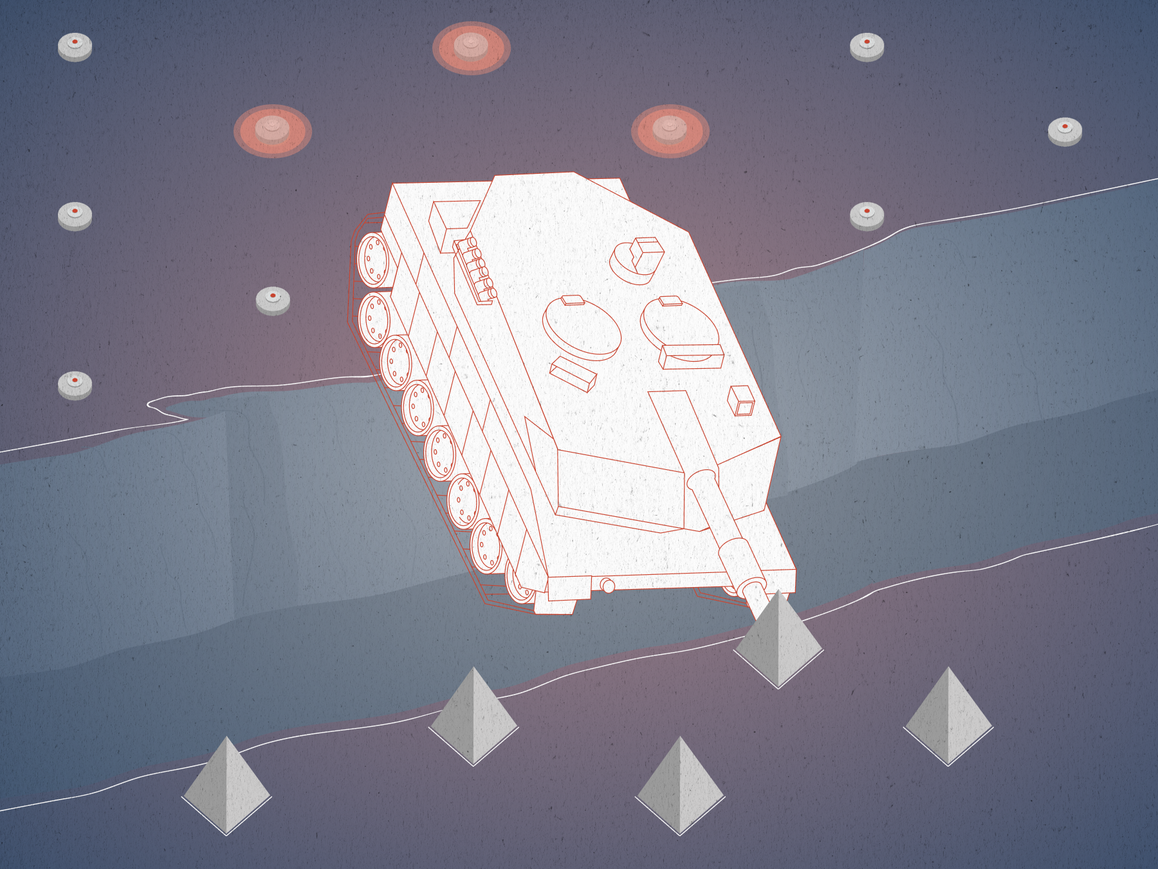

That short tactical success exposed gaps in Ukraine’s defense: enemy reconnaissance elements slipped through strongpoints of the “new Donbas line,” a system of fortifications built in recent months. Minefields, long rows of concrete “Toblerone” obstacles, and coils of barbed wire augment natural barriers. Earthen berms and anti-tank ditches are meant to slow wheeled and tracked vehicles. But, NZZ concedes, engineers clearly underrated motorcycles: near Zolotyi Kolodiaz, assault groups punched through even a second line and reached the connecting route between Kramatorsk and Pokrovsk. Only units of a Ukrainian airmobile brigade managed to clear this “lifeline” of enemy troops.

Defense as a Diplomatic Argument

The “new Donbas line” was supposed to relieve infantry and artillery. The military “math” is familiar: an attacker hitting a fortified position needs five times the force, and on difficult terrain, up to nine times. But how much of this complex has actually been built? If necessary, could forces fall back to these lines in good order?

Kyiv is carefully concealing the scale of the works—and with good reason: the less the enemy knows, the better the odds for the defense. The General Staff has not published a consolidated map; the reason is OPSEC—operational security. The most detailed public schematic came from French student Clément Molin, who analyzed available commercial satellite imagery. In NZZ’s assessment, cross-checking his map against medium-resolution imagery shows a high degree of accuracy in the plotted fortifications. The conclusion: the entire front line appears to be covered, with the strongest segments in Donbas.

The timeline matters, too. NZZ notes that serious digging began only at the start of the year—late. In February, for example, around the village of Torske near the Lyman junction, there were still no fortifications; by July, the main trench had been cut “in one continuous line.” Mines and concrete pieces aren’t visible from orbit, but the earthworks are.

Schematically, the “belt” mirrors the terrain. The key link is a chain of four cities from Sloviansk to Kostyantynivka. Three of them sit on the Kazennyi Torets, a tributary of the Siverskyi Donets. Rivers and forests dictate combat possibilities along today’s front; in Kramatorsk, the main supply rail lines converge.

Behind this “urban bastion” lies the Donbas line in the strict sense: a double barrier designed for the worst case—a broad breakthrough. If the enemy “bores through” the built-up area, movement along the rivers can accelerate. Hence these are the true last-resort fortifications. Parallel to the front, Ukrainian engineers also try to “channel” the attacker with obstacles oriented along likely axes of advance from the southeast to the northwest. That chokes off lateral shifts and mutual support among assault groups: maneuver is harder, predictability higher.

Three Operational Factors: Time, Space, Force

NZZ suggests viewing the situation through the classic triad—time, space, and force:

- Time. Ukraine delayed a full-scale fortification cycle—and that narrows its own options for sudden offensive action. In NZZ’s view, after the public humiliation of Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House in late February, Kyiv effectively stopped counting on a “big counteroffensive” and pivoted to defense.

- Space. Between Kostyantynivka and Dobropillia, judging by maps and events in August, there was a “gap” the enemy exploited. On some stretches, NZZ writes, Russian units still hang “on the far side” of the major earthen barriers. The operational command in Donbas, it seems, was itself surprised by success and failed to feed in reserves on time.

- Force. General Syrskyi is trying to lift spirits precisely on this segment. This week he said the newly formed corps in the Donetsk operational zone is now working “in the designated composition.” The message: there are enough troops in this sector. From the outside, that claim cannot be verified.

Politics vs. Geography

Kyiv is demonstrably unwilling to yield the partially occupied regions—directly contradicting Moscow’s conditions. Vladimir Putin demands a Ukrainian pullout from Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson, so that Russian forces can occupy positions up to the “new Donbas line” without a fight. As NZZ notes, the point isn’t a few tracts of land but the restoration of an “imperial project.”

Diplomacy, in the Kremlin’s use, NZZ argues, becomes the continuation of the offensive—by “other means” that improve the start position for the next phase of combat. Just as difficult as leaving all of Donetsk would be “giving up” Kherson: in that case Russian forces could force the Dnipro, entrench on the west bank, and eventually loom over Odesa and the entire Black Sea arc.

Yet neither Moscow nor Kyiv, judging by the front’s dynamics, is betting on that scenario. The Russian army keeps massing around the Kramatorsk hub, trying to “close a cauldron” in Donbas. A push toward Sumy or Kharkiv can’t be ruled out—Syrskyi needs free reserves. There are few opportunities to “cool” the fighting operationally via organized withdrawal and reconstitution.

Withdrawal as an Option—and Its Limits

If necessary, thanks to the fortifications, defenders could exit Pokrovsk without panic, NZZ believes—avoiding a pincer. But the commander-in-chief knows: retaking lost ground will be extremely hard. The obvious conclusion: Ukraine needs even longer and stronger fortifications—along the whole front and on the border with Belarus. Satellite images NZZ points to show construction has not stopped in recent weeks.

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump is encouraging Kyiv to strike targets in Russia—with cruise missiles, rocket artillery, drones, and perhaps even combat aircraft. But “on the ground,” this will change little in the near term. Kyiv’s main “insurance policy” is not promises but concrete, trenches, and mines: its own fortifications as a guarantee against an imposed “dictated peace.”

This article was prepared based on materials published by Neue Zürcher Zeitung. The author does not claim authorship of the original text but presents their interpretation of the content for informational purposes.

The original article can be found at the following link: Neue Zürcher Zeitung.

All rights to the original text belong to Neue Zürcher Zeitung.