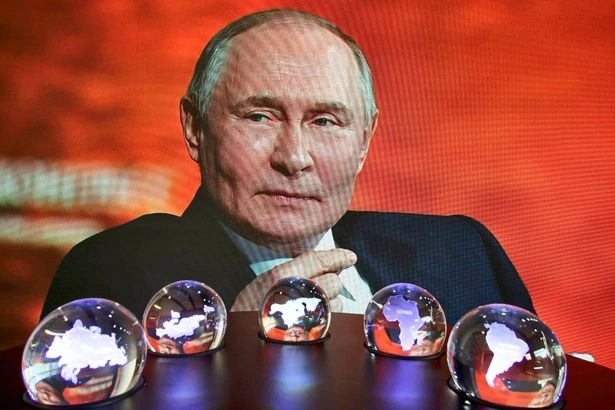

The war between Russia and Ukraine has entered a protracted phase. The front lines have barely shifted, casualties are high on both sides, and Vladimir Putin’s rhetoric remains uncompromising. At the St. Petersburg Economic Forum in June 2025, he once again articulated his central ideological stance:

“I see the Russian and Ukrainian peoples as one people. In this sense, all of Ukraine belongs to us.”

This is not mere rhetoric — it reflects the Kremlin’s enduring ambitions. Yet amid growing internal pressure, limited resources, and international isolation, experts are increasingly asking: could 2026 be the year when the Kremlin starts looking for a way out of the war — not to surrender, but perhaps to pause?

The Austrian outlet Der Standard posed this question to two influential analysts: Emily Ferris from the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), and Mark Galeotti, one of the UK’s leading Russia experts. Their perspectives differ, but together they form a multidimensional analysis of what could drive Putin to shift course in 2026.

❖ Ferris: The failure of “reunification” threatens the regime itself

According to Emily Ferris, the Kremlin has failed to achieve its original strategic objectives in Ukraine. Russia controls about 20% of Ukrainian territory, but this figure has remained nearly unchanged for three years. More importantly, Ferris notes, the goal was never just territorial — it was ideological: the “reunification” of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus.

“If Putin abandons this idea, he undermines one of the core pillars of his own legitimacy,” Ferris says.

In this sense, the question of ending the war is directly tied to the survival of the regime. But if the system begins to overheat, a tactical recalibration may become necessary. That opens the door to a possible scenario: a temporary ceasefire in 2026 — not a concession, but a strategic pause.

“I can imagine that in 2026, a ceasefire could become attractive for Russia. That would allow Moscow to outwait the Trump administration — and later try to achieve regime change in Kyiv through political means,” she suggests.

Still, Ferris emphasizes that such a move would only happen if it offers Russia clear unilateral advantages. There’s no room for honest compromise — Putin would only be willing to slow the war if it strengthened, not weakened, his position.

❖ Galeotti: The front is stuck, but the economy is overheating

Mark Galeotti takes a different view. He doesn’t believe Ukraine will be able to force Russia into retreat on the battlefield — but he does see internal economic pressure as a potentially decisive factor.

“He wasn’t ready to negotiate even when he lost territory near Kursk. If Ukraine threatens the land bridge to Crimea — that could get his attention. But that scenario is unlikely,” he argues.

The economic factor, by contrast, is far more tangible. According to Galeotti, by 2026 Russia will likely have exhausted its stocks of Soviet-era military equipment, while manufacturing and purchasing new weapons will be extremely costly.

“We’re approaching stagflation. Perhaps as early as late 2025 or in 2026, the question will arise: ‘guns or butter?’”

At that point, he predicts, public fatigue could quietly build. He sees no imminent threat to the regime — Russia’s political system is structured so that all branches of power monitor each other, and no one dares take the first step. But a decline in military capability and growing internal dissatisfaction are trends the Kremlin cannot ignore.

“The Prigozhin mutiny showed the army wasn’t willing to defend Putin — but also wasn’t ready to rise against him. It was a gesture of neutrality, not rebellion,” Galeotti notes.

❖ China: A silent partner profiting from a prolonged war

Both experts point to an important external factor — China. While many in the West still hope Beijing could push Putin toward peace or act as a mediator, both Ferris and Galeotti firmly reject that idea.

“Xi Jinping voices concern about the war’s economic consequences, but in reality, China has strengthened its position. It has expanded its leverage over Moscow. If Xi tried to dictate terms, the relationship could quickly unravel,” explains Ferris.

Galeotti adds:

“This is a good war for China. It distracts the West, makes Russia more dependent, and may allow Beijing to step in as peacemaker — if the West fails.”

In short, China has no interest in ending the war. It benefits from the status quo — and thus won’t act as a restraining force on the Kremlin. If anything, it helps sustain Moscow’s ability to keep going.

❖ Three Vectors of Pressure — Why 2026 Could Shift the Kremlin’s Calculus

When combining the three key vectors — internal ideological stress (Ferris), economic depletion (Galeotti), and external inertia bolstered by Chinese support, it becomes clearer why 2026 could be a turning point.

Putin isn’t seeking peace — but he may seek a pause. Not because he’s lost, but because even the most resilient system occasionally needs to retreat in order to advance later.

“From Putin’s perspective, time is a resource. He can afford to wait. But can he afford to lose?” — the question remains open.

And 2026 may be the moment when the Kremlin, for the first time in years, feels compelled to give up something — just to hold on to the rest.

This article was prepared based on materials published by Der Standard. The author does not claim authorship of the original text but presents their interpretation of the content for informational purposes.

The original article can be found at the following link: Der Standard.

All rights to the original text belong to Der Standard.